9 Working With Color Is an Art but Not Science

In the visual arts, color theory is a body of practical guidance to colour mixing and the visual effects of a specific color combination. Colour terminology based on the color cycle and its geometry separates colors into chief color, secondary colour, and tertiary colour. Agreement color theory dates to antiquity. Aristotle (d. 322 BCE) and Claudius Ptolemy (d. 168 CE) already discussed which and how colors can exist produced by mixing other colors. The influence of light on color was investigated and revealed further by al-Kindi (d. 873) and Ibn al-Haytham (d.1039). Ibn Sina (d. 1037), Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (d. 1274) and Robert Grosseteste (d. 1253) discovered that contrary to the teachings of Aristotle, at that place are multiple color paths to get from black to white[1]. [ii] More modern approaches to color theory principles tin can be constitute in the writings of Leone Battista Alberti (c. 1435) and the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1490). A formalization of "colour theory" began in the 18th century, initially inside a partisan controversy over Isaac Newton's theory of color (Opticks, 1704) and the nature of principal colors. From there it developed as an independent creative tradition with but superficial reference to colorimetry and vision science.[ citation needed ]

The application of color theory ranges from aboriginal Egyptian uses to mod commercial advertising. Colors touch our mood and perception. In ancient civilizations, color was explored for its healing backdrop. Phototherapy (light therapy) was practiced in ancient Arab republic of egypt, Hellenic republic, China and Republic of india. The Egyptians utilized sunlight equally well every bit color for healing.[3] Colour has been investigated for its healing potential since 2000 BC.[four]

Classifications [edit]

Color tin be classified according to

- Warm and Cold

- Receding and Advancing

- Positive and negative

- Subtractive and additive

Color abstractions [edit]

The foundations of pre-20th-century color theory were built around "pure" or ideal colors, characterized by unlike sensory experiences rather than attributes of the concrete earth. This has led to a number of inaccuracies in traditional colour theory principles that are not always remedied in mod formulations.[5]

Another issue has been the tendency to describe color furnishings holistically or categorically, for example as a contrast between "yellow" and "bluish" conceived as generic colors, when near color effects are due to contrasts on three relative attributes which define all colors:

- Value (lite vs. dark, or white vs. blackness),

- Blush [saturation, purity, strength, intensity] (intense vs. dull), and

- Hue (due east.g. the name of the color family: cerise, yellow, green, cyan, blue, magenta).

The visual bear on of "yellow" vs. "blueish" hues in visual pattern depends on the relative lightness and saturation of the hues.

These confusions are partly historical and arose in scientific doubt most the color perception that was not resolved until the late 19th-century when the creative notions were already entrenched. They besides arise from the endeavour to depict the highly contextual and flexible beliefs of colour perception in terms of abstract color sensations that tin can be generated equivalently by whatever visual media.

Many historical "color theorists" have assumed that 3 "pure" principal colors tin can mix into all possible colors, and any failure of specific paints or inks to friction match this platonic performance is due to the impurity or imperfection of the colorants. In reality, only imaginary "primary colors" used in colorimetry can "mix" or quantify all visible (perceptually possible) colors; only to do this, these imaginary primaries are defined as lying outside the range of visible colors; i.e., they cannot exist seen. Whatsoever 3 real "primary" colors of lite, paint or ink can mix merely a limited range of colors, called a gamut, which is e'er smaller (contains fewer colors) than the full range of colors humans can perceive.[6]

Historical background [edit]

Color theory was originally formulated in terms of iii "main" or "primitive" colors—carmine, xanthous and blue (RYB)—because these colors were believed capable of mixing all other colors.[vii]

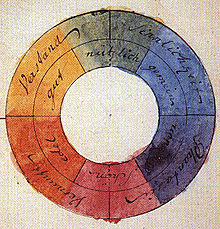

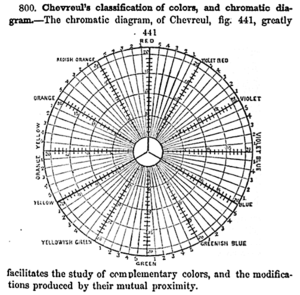

The RYB primary colors became the foundation of 18th-century theories of color vision,[ citation needed ] as the fundamental sensory qualities that are composite in the perception of all physical colors, and conversely, in the physical mixture of pigments or dyes. These theories were enhanced by 18th-century investigations of a multifariousness of purely psychological color furnishings, in particular the contrast between "complementary" or opposing hues that are produced past colour afterimages and in the contrasting shadows in colored calorie-free. These ideas and many personal color observations were summarized in two founding documents in colour theory: the Theory of Colours (1810) by the High german poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and The Police of Simultaneous Color Contrast (1839) by the French industrial chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. Charles Hayter published A New Practical Treatise on the Three Archaic Colours Assumed equally a Perfect System of Rudimentary Information (London 1826), in which he described how all colors could exist obtained from just 3.

Page from 1826 A New Practical Treatise on the Three Primitive Colours Assumed as a Perfect Organization of Rudimentary Information by Charles Hayter

Subsequently, German and English language scientists established in the late 19th century that color perception is best described in terms of a different gear up of primary colors—scarlet, light-green and blue-violet (RGB)—modeled through the additive mixture of iii monochromatic lights. Subsequent research anchored these primary colors in the differing responses to lite by iii types of colour receptors or cones in the retina (trichromacy). On this basis the quantitative description of the color mixture or colorimetry developed in the early 20th century, along with a serial of increasingly sophisticated models of colour infinite and color perception, such every bit the opponent process theory.

Beyond the same period, industrial chemical science radically expanded the color range of lightfast synthetic pigments, allowing for essentially improved saturation in color mixtures of dyes, paints, and inks. It besides created the dyes and chemic processes necessary for color photography. As a result, three-color press became aesthetically and economically feasible in mass printed media, and the artists' color theory was adjusted to principal colors nigh effective in inks or photographic dyes: cyan, magenta, and yellow (CMY). (In press, dark colors are supplemented past black ink, known equally the CMYK organisation; in both printing and photography, white is provided by the color of the paper.) These CMY primary colors were reconciled with the RGB primaries, and subtractive color mixing with condiment color mixing, past defining the CMY primaries as substances that captivated just one of the retinal main colors: cyan absorbs only reddish (−R+K+B), magenta only dark-green (+R−K+B), and yellow simply blue-violet (+R+G−B). It is important to add that the CMYK, or process, color printing is meant every bit an economical way of producing a wide range of colors for printing, merely is scarce in reproducing certain colors, notably orange and slightly scarce in reproducing purples. A wider range of colors tin exist obtained with the improver of other colors to the printing process, such every bit in Pantone's Hexachrome printing ink system (half-dozen colors), amidst others.

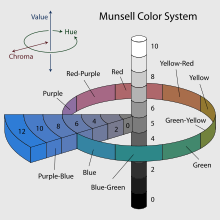

Munsell's 1905 color system represented as a three-dimensional solid showing all three color making attributes: lightness, saturation and hue.

For much of the 19th-century creative colour theory either lagged behind scientific understanding or was augmented past science books written for the lay public, in particular Modern Chromatics (1879) by the American physicist Ogden Rood, and early on colour atlases developed past Albert Munsell (Munsell Book of Color, 1915, see Munsell color system) and Wilhelm Ostwald (Color Atlas, 1919). Major advances were made in the early 20th century by artists teaching or associated with the German language Bauhaus, in detail Wassily Kandinsky, Johannes Itten, Faber Birren and Josef Albers, whose writings mix speculation with an empirical or demonstration-based report of color design principles.

Traditional color theory [edit]

Complementary colors [edit]

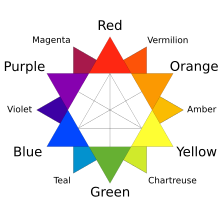

For the mixing of colored light, Isaac Newton's color wheel is often used to depict complementary colors, which are colors that cancel each other's hue to produce an achromatic (white, grayness or black) light mixture. Newton offered as a conjecture that colors exactly contrary i some other on the hue circle cancel out each other's hue; this concept was demonstrated more thoroughly in the 19th century. An example of complementary colors would be red and light-green[8]

A key assumption in Newton'southward hue circle was that the "fiery" or maximum saturated hues are located on the outer circumference of the circle, while achromatic white is at the heart. And then the saturation of the mixture of two spectral hues was predicted past the direct line between them; the mixture of three colors was predicted by the "center of gravity" or centroid of three triangle points, and so on.

According to traditional color theory based on subtractive primary colors and the RYB color model, yellow mixed with regal, orangish mixed with blueish, or red mixed with dark-green produces an equivalent grayness and are the painter's complementary colors. These contrasts grade the footing of Chevreul's law of color contrast: colors that appear together will be altered as if mixed with the complementary colour of the other color. A slice of xanthous cloth placed on a blue background will announced tinted orange considering orange is the complementary color to bluish.

However, when complementary colors are chosen based on the definition by lite mixture, they are non the same as the artists' primary colors. This discrepancy becomes of import when color theory is practical beyond media. Digital color management uses a hue circle divers according to additive primary colors (the RGB color model), as the colors in a figurer monitor are additive mixtures of lite, not subtractive mixtures of paints.

One reason the artist's principal colors piece of work at all is due to the imperfect pigments existence used have sloped absorption curves, and alter color with concentration. A pigment that is pure red at loftier concentrations tin can behave more than like magenta at low concentrations. This allows information technology to make purples that would otherwise be incommunicable. Likewise, a bluish that is ultramarine at high concentrations appears cyan at low concentrations, allowing information technology to be used to mix greenish. Chromium red pigments can appear orangish, and then yellow, every bit the concentration is reduced. It is fifty-fifty possible to mix very depression concentrations of the blue mentioned and the chromium reddish to get a greenish colour. This works much better with oil colors than it does with watercolors and dyes.

The sometime primaries depend on sloped absorption curves and pigment leakages to work, while newer scientifically derived ones depend solely on decision-making the amount of absorption in certain parts of the spectrum.

Another reason the right primary colors were not used by early artists is they were not available every bit durable pigments. Mod methods in chemistry were needed to produce them.

Warm vs. absurd colors [edit]

The distinction betwixt "warm" and "absurd" colors has been important since at least the late 18th century.[9] The difference (as traced by etymologies in the Oxford English Dictionary), seems related to the observed contrast in mural light, between the "warm" colors associated with daylight or sunset, and the "absurd" colors associated with a gray or overcast day. Warm colors are frequently said to be hues from ruby-red through xanthous, browns, and tans included; cool colors are often said to be the hues from bluish-green through blue violet, nearly grays included. There is a historical disagreement about the colors that anchor the polarity, but 19th-century sources put the peak contrast between cherry-red-orange and greenish-blue.

Color theory has described perceptual and psychological furnishings to this contrast. Warm colors are said to advance or appear more active in a painting, while cool colors tend to recede; used in interior pattern or manner, warm colors are said to agitate or stimulate the viewer, while absurd colors calm and relax.[10] Near of these effects, to the extent they are real, can be attributed to the higher saturation and lighter value of warm pigments in dissimilarity to cool pigments; brown is a dark, unsaturated warm color that few people recollect of as visually agile or psychologically arousing.

The traditional warm/cool association of a color is reversed relative to the color temperature of a theoretical radiating black trunk; the hottest stars radiate blue (cool) light, and the coolest radiate red (warm) light.

The hottest radiating bodies (e.g. stars) have a "cool" color, while the less hot bodies radiate with a "warm" colour. (image is in Kelvin calibration)

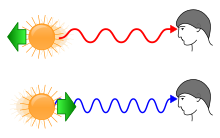

This dissimilarity is further seen in the psychological associations of colors with the Doppler upshot seen in astronomical objects. Traditional psychological associations, where warm colors are associated with advancing objects and cool colors with receding objects, are straight opposite those seen in astrophysics, where stars or galaxies moving towards our viewpoint on World are blueshifted (advancing) and stars or galaxies moving away from Earth are redshifted (receding).

Achromatic colors [edit]

Any color that lacks potent chromatic content is said to be unsaturated, achromatic, almost-neutral, or neutral. Near neutrals include browns, tans, pastels, and darker colors. Almost neutrals can be of any hue or lightness. Pure achromatic, or neutral colors include blackness, white and all grays.

Near neutrals are obtained by mixing pure colors with white, blackness or grey, or by mixing two complementary colors. In color theory, neutral colors are easily modified by adjacent more saturated colors and they appear to take on the hue complementary to the saturated color; e.g., next to a bright red couch, a gray wall will announced distinctly greenish, This is a property of human being vision.

Blackness and white accept long been known to combine "well" with almost whatever other colors; black decreases the apparent saturation or brightness of colors paired with it and white shows off all hues to equal upshot.[ citation needed ]

Tints and shades [edit]

When mixing colored calorie-free (additive color models), the achromatic mixture of spectrally balanced reddish, greenish, and blue (RGB) is always white, not gray or black. When we mix colorants, such equally the pigments in paint mixtures, a color is produced which is always darker and lower in chroma, or saturation, than the parent colors. This moves the mixed colour toward a neutral colour—a greyness or near-black. Lights are made brighter or dimmer by adjusting their effulgence, or energy level; in painting, lightness is adjusted through mixture with white, black, or a color's complement.

It is common among some painters to darken a paint color by adding black paint—producing colors called shades—or lighten a color by calculation white—producing colors called tints. However, it is not always the all-time way for representational painting, as an unfortunate issue is for colors to also shift in hue. For instance, darkening a color by adding black tin can cause colors such equally yellows, reds, and oranges, to shift toward the greenish or blue office of the spectrum. Lightening a color by calculation white tin cause a shift towards blue when mixed with reds and oranges. Another do when darkening a color is to apply its opposite, or complementary, color (eastward.g. purplish-red added to yellowish-dark-green) in society to neutralize it without a shift in hue, and darken it if the additive color is darker than the parent colour. When lightening a color this hue shift can be corrected with the add-on of a pocket-size corporeality of an adjacent colour to bring the hue of the mixture back in line with the parent color (eastward.yard. adding a pocket-size amount of orangish to a mixture of blood-red and white will correct the tendency of this mixture to shift slightly towards the blue end of the spectrum).

Split chief colors [edit]

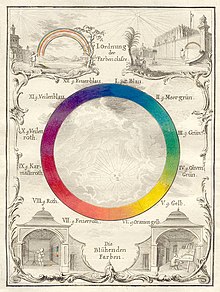

In painting and other visual arts, ii-dimensional color wheels or three-dimensional color solids are used as tools to teach beginners the essential relationships betwixt colors. The organisation of colors in a particular color model depends on the purpose of that model: some models show relationships based on human color perception, whereas others are based on the color mixing properties of a particular medium such as a figurer display or set of paints.

This organization is still popular among contemporary painters,[ citation needed ] every bit it is basically a simplified version of Newton's geometrical dominion that colors closer together on the hue circumvolve will produce more than vibrant mixtures. However, with the range of contemporary paints available, many artists merely add more paints to their palette as desired for a variety of practical reasons. For example, they may add together a scarlet, regal and/or greenish paint to expand the mixable gamut; and they include ane or more dark colors (specially "earth" colors such equally yellow ochre or burnt sienna) merely because they are convenient to have premixed.[ citation needed ] Printers normally augment a CMYK palette with spot (trademark specific) ink colors.

Colour harmony [edit]

Information technology has been suggested that "Colors seen together to produce a pleasing affective response are said to be in harmony".[eleven] Even so, color harmony is a complex notion because human being responses to color are both melancholia and cerebral, involving emotional response and judgment. Hence, our responses to color and the notion of colour harmony is open to the influence of a range of unlike factors. These factors include private differences (such every bit historic period, gender, personal preference, affective land, etc.) as well as cultural, sub-cultural, and socially-based differences which gives rise to conditioning and learned responses nearly color. In addition, context always has an influence on responses most color and the notion of color harmony, and this concept is likewise influenced past temporal factors (such as changing trends) and perceptual factors (such equally simultaneous contrast) which may impinge on human response to color. The following conceptual model illustrates this 21st-century approach to colour harmony:

wherein color harmony is a part (f) of the interaction betwixt color/s (Col i, 2, 3, …, n) and the factors that influence positive aesthetic response to color: individual differences (ID) such equally age, gender, personality and melancholia country; cultural experiences (CE), the prevailing context (CX) which includes setting and ambient lighting; intervening perceptual effects (P) and the furnishings of fourth dimension (T) in terms of prevailing social trends.[12]

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. Göttingen, 1775, plate III.

In addition, given that humans tin perceive over two.8 meg different colors,[13] it has been suggested that the number of possible colour combinations is virtually space thereby implying that predictive colour harmony formulae are fundamentally unsound.[xiv] Despite this, many color theorists accept devised formulae, principles or guidelines for color combination with the aim being to predict or specify positive aesthetic response or "color harmony".

Color wheel models accept frequently been used equally a ground for color combination principles or guidelines and for defining relationships between colors. Some theorists and artists believe juxtapositions of complementary color volition produce strong dissimilarity, a sense of visual tension equally well as "color harmony"; while others believe juxtapositions of coordinating colors will elicit a positive aesthetic response. Color combination guidelines (or formulas) suggest that colors next to each other on the color wheel model (analogous colors) tend to produce a single-hued or monochromatic colour experience and some theorists besides refer to these as "uncomplicated harmonies".[fifteen]

In addition, split complementary colour schemes usually depict a modified complementary pair, with instead of the "truthful" second color being called, a range of analogous hues effectually it are chosen, i.eastward. the divide complements of ruby are blue-green and yellow-greenish. A triadic colour scheme adopts whatsoever three colors approximately equidistant around a color wheel model. Feisner and Mahnke are among a number of authors who provide color combination guidelines in greater detail.[16] [17]

Ignaz Schiffermüller, Versuch eines Farbensystems (Vienna, 1772), plate I.

Color combination formulae and principles may provide some guidance merely accept express applied application. This is due to the influence of contextual, perceptual, and temporal factors which will influence how color/s are perceived in any given situation, setting, or context. Such formulae and principles may be useful in fashion, interior and graphic design, only much depends on the tastes, lifestyle, and cultural norms of the viewer or consumer.

As early as the ancient Greek philosophers, many theorists have devised color associations and linked item connotative meanings to specific colors.[18] However, connotative color associations and colour symbolism tends to be culture-bound and may also vary across dissimilar contexts and circumstances. For example, red has many unlike connotative and symbolic meanings from exciting, arousing, sensual, romantic, and feminine; to a symbol of practiced luck; and too acts as a signal of danger. Such color associations tend to be learned and practise not necessarily agree irrespective of individual and cultural differences or contextual, temporal or perceptual factors.[xix] It is important to notation that while color symbolism and color associations exist, their being does non provide evidential support for color psychology or claims that color has therapeutic properties.[20]

Monochromatic [edit]

The monochromatic formula chooses only 1 color (or hue). Variations of the color are created by irresolute the value and saturation of the color. Since only ane hue is used, the color and its variations are guaranteed to piece of work.

Current status [edit]

Color theory has not adult an explicit explanation of how specific media touch color advent: colors have always been defined in the abstract, and whether the colors were inks or paints, oils or watercolors, transparencies or reflecting prints, computer displays or movie theaters, was not considered particularly relevant.[21] Josef Albers investigated the effects of relative contrast and color saturation on the illusion of transparency, but this is an exception to the rule.[22]

See also [edit]

- Additive color

- Charles Albert Keeley

- Color Field

- Colour management

- Colour mixing

- Colour psychology

- Color scheme

- Color wheel

- Color charge

- Complementary colors

- HSV colour space

- On Vision and Colors

- Paint sheen

- Subtractive color

- Tints and shades

References [edit]

- ^ Smithson, H.E.; Dinkova-Bruun, G.; Gasper, G.E.M.; Huxtable, Chiliad.; McLeish, T.C.B.; Panti, C.P. (2012). "A three-dimensional color infinite from the 13th century". J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 29 (two): A346–A352. Bibcode:2012JOSAA..29A.346S. doi:10.1364/josaa.29.00A346. PMC3287286. PMID 22330399.

- ^ Kirchner, E. (2013). "Color theory and colour order in medieval Islam: A review". Colour Research & Awarding. twoscore (1): 5-16. doi:10.1002/col.21861.

- ^ "A comparative written report on the treatment of migraine headache with combined distant and local acupuncture points versus conventional drug therapy Shuyuan G, Donglan Z, Yanguang X. Am J Acupunct 1999;27:27?30". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 23 (v): 376–377. June 2000. doi:10.1016/s0161-4754(00)90237-9. ISSN 0161-4754.

- ^ Joann., Eckstut (22 October 2013). The cloak-and-dagger language of colour : scientific discipline, nature, history, civilisation, beauty of scarlet, orangish, yellow, dark-green, bluish & violet. ISBN978-1-57912-949-one. OCLC 828893320.

- ^ "handprint : colormaking attributes". www.handprint.com . Retrieved 2021-07-31 .

- ^ "Traditional and Modern Colour Theory Part i: Modern Colour Theory". Retrieved 2021-ten-xv .

- ^ "The History of Colour Theory: Must-Know Facts for Creatives - Pigment Pool". Retrieved 2021-07-31 .

- ^ "The History of Colour Theory: Must-Know Facts for Creatives - Pigment Pool". Retrieved 2021-07-31 .

- ^ "colour temperature". handprint. 2009-04-19. Retrieved 2011-06-09 .

- ^ Singh, Satyendra (2006-01-01). "Impact of colour on marketing". Management Determination. 44 (6): 783–789. doi:ten.1108/00251740610673332. ISSN 0025-1747.

- ^ Burchett, K. Due east. (2002). "Colour Harmony". Color Research and Application, 27 (ane), pp. 28–31.

- ^ O'Connor, Z. (2010). "Color harmony revisited". Color Inquiry and Application, 35 (iv), pp. 267–273.

- ^ Pointer, M. R. & Attridge, One thousand.1000. (1998). "The number of discernible colors". Colour Inquiry and Application, 23 (1), pp. 52–54.

- ^ Difficult, A. & Sivik, L. (2001). "A theory of colors in combination – A descriptive model related to the NCS color-gild organisation". Color Inquiry and Awarding, 26 (1), pp. 4–28.

- ^ Garau, Augusto (1993). Color Harmonies . University of Chicago press. p. seven. ISBN0226281965.

- ^ Feisner, Eastward. A. (2000). Colour: How to apply colour in art and blueprint. London: Laurence Rex.

- ^ Mahnke, F. (1996). Colour, environment and human response. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Benson, J. Fifty. (2000). "Greek Color Theory and the Iv Elements [full text, not including figures]". Greek Color Theory and the Iv Elements.

- ^ Bellantoni, Patti (2005). If it'due south Majestic, Someone's Gonna Die. Elsevier, Focal Press. ISBN0-240-80688-three.

- ^ O'Connor, Z. (2010). "Color psychology and color therapy: Caveat emptor". Color Enquiry and Application

- ^ "Pigments through the Ages - Renaissance and Baroque (1400-1600)". www.webexhibits.org.

- ^ Albers, Josef (2006). Interaction of Color. Revised and Expanded Edition. Yale University Printing. ISBN0-300-11595-iv.

External links [edit]

- Color Theory Tutorial by Worqx

- Handprint.com : Color – a comprehensive site about colour perception, color psychology, color theory, and color mixing

- Color Differences

- Color Theory in Landscape Design

- The Dimensions of Colour – colour theory for artists using digital/ traditional media

- Colour Thesaurus Earth's Largest Database of Color Names

- Stanford University CS 178 interactive Flash demo introducing trichromatic colour theory.

- App that generates harmonious color palettes from photos based on color theory

- Color theory as information technology relates to interior decorating

- Applying Colour Theory to Digital Media and Visualization – a book from CRC Press

flemingpontliatich.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_theory

0 Response to "9 Working With Color Is an Art but Not Science"

Post a Comment